Arbitration law in 2024: a review

Arbitration law in 2024: a review

Commencing arbitration and arbitrability

Is there a dispute? “It takes two to tango”

Has the alternative dispute resolution mechanism clause been superseded?

Who decides – the tribunal or the court?

Scope of arbitration clauses – can tort claims be covered?

Pathological clauses – are they salvageable?

Exclusive jurisdiction clauses (in addition to arbitration clauses)

Multiple party/multiple contract arbitrations

Court-mandated alternative dispute resolution

Is the tribunal functus officio?

Are damages available for breach of implied promise to honour award?

When tribunals did not but should have assumed jurisdiction

Revised IBA Guidelines on Conflicts of Interest in International Arbitration

Challenging the award: substantive jurisdiction (section 67)

Challenging the award: serious irregularity (section 68)

Non-disclosure by an arbitrator

Appeal on point of law (section 69)

Court assistance and intervention

Anti-suit/ arbitration injunctions

Effect of Consumer Rights Act 2015

Failure to comply with procedural orders

Investor-state dispute settlement

Updates to other arbitration laws

Singapore International Arbitration Centre (SIAC)

Hong Kong International Arbitration Centre (HKIAC)

Shanghai International Arbitration Center (SHIAC)

China International Economic and Trade Arbitration Commission (CIETAC)

Developments in relation to how arbitrations can be funded

Trends in 2024, and what 2025 might hold in store for arbitration

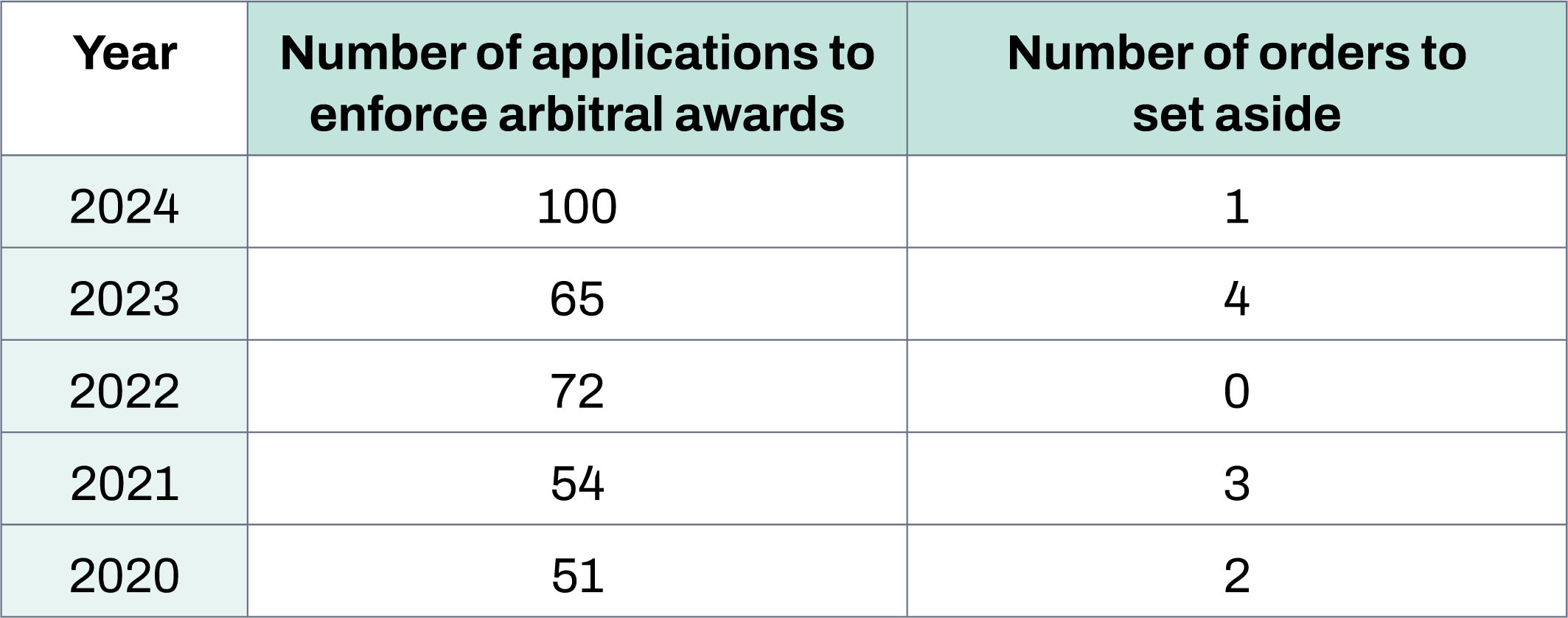

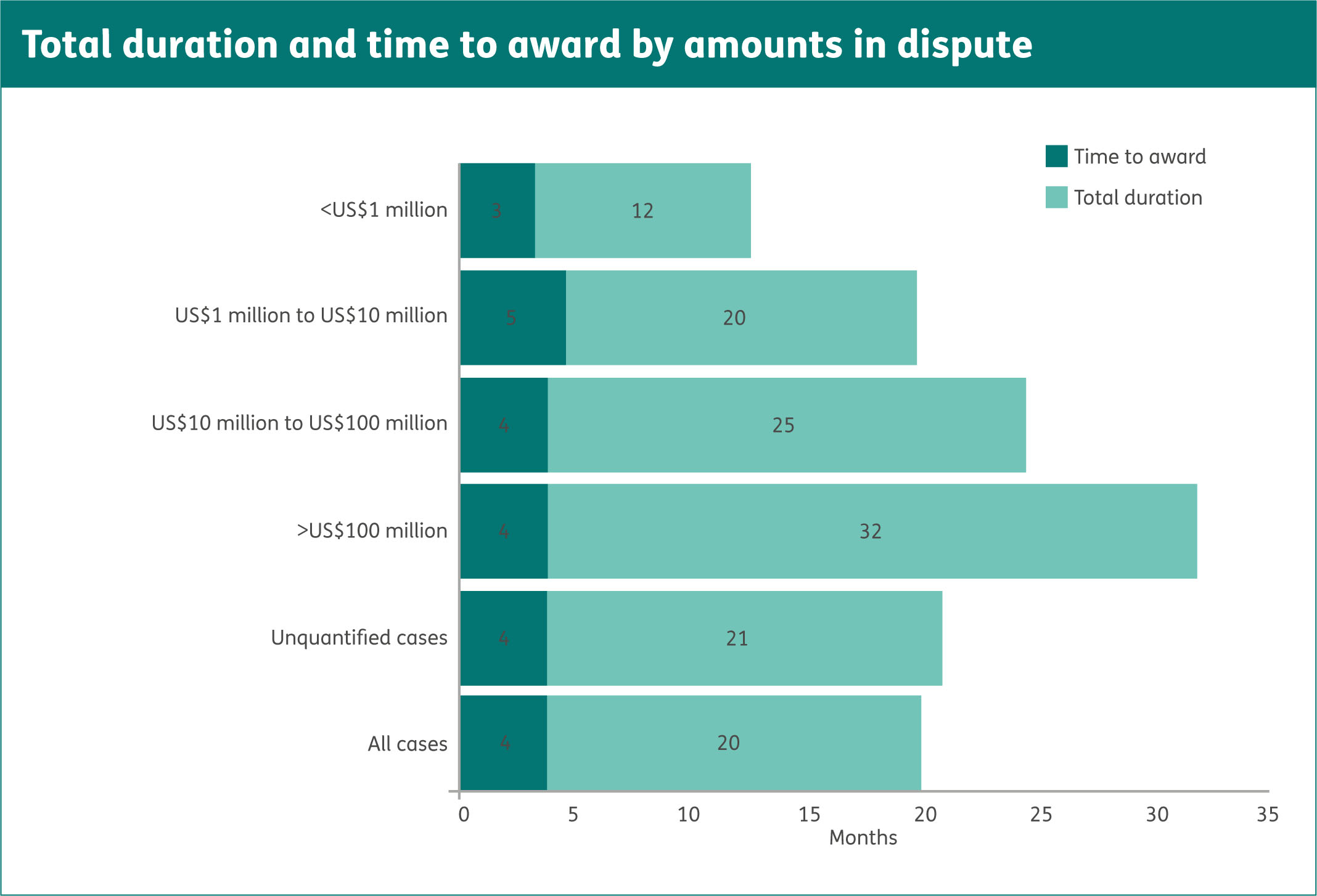

Statistics from the leading arbitral institutions

Conflicting decisions on winding up and arbitration

Introduction

This year’s review covers the court decisions and developments in the field of arbitration in 2024 which caught our attention, focusing more on commercial arbitration than investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS). It follows our first review in relation to 2023.1 Conceptually the review is like an organised scrapbook with commentary on why 2024 developments are relevant. What will quickly be clear to readers is that the body of international arbitration law and practice continues to grow. Thus, while this review definitely is longer than last year’s edition, it does not try to be exhaustive.

In terms of jurisdictions covered, since we are mainly based in Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China (Hong Kong) and England, our review focuses on covering case law and trends in those jurisdictions as well as in other key common law arbitration seat jurisdictions including Singapore. We will occasionally cover leading cases from elsewhere especially by way of juxtaposition or underlining global trends. In particular, for the second time we provide an update on the law on winding up and arbitration across key common law jurisdictions.

By way of structure and content, this review again analyses cases in a sequence that mirrors the structure and chronology of a dispute resolved through arbitration – ie starting with the commencement of an arbitration and ending with the enforcement of a foreign award by a court. There is also a section on relief granted by courts in aid of arbitration. As last year, we also cover other major developments such as the Arbitration Act 2025 (which received Royal Assent on 24 February 2025), amendments to major arbitral rules (notably by SIAC and HKIAC) and developments in relation to how arbitrations can be funded (including PACCAR). Moreover, this review briefly covers major legal developments in China, India and Malaysia and other jurisdictions that are on our radar.

In a final section we seek to summarise the trends we have identified and suggest what 2025 might hold in store for arbitration. Since we released our first edition of this review last year, we can now assess our tea leaf reading abilities for the first time (and do this below).

Did our predictions for 2024 come true?

The short answer is that some of them did not – yet – whereas most of them did. Notably the Arbitration Act 2025 received Royal Assent in February 2025. Also 2024 cases reconfirm that parties should indeed be mindful of procedural matters including respecting timeframes to appeal. Interestingly, 2024 developments suggest that arbitrators too should be careful – especially as regards disclosures and avoiding prematurely becoming functus officio (eg by express reservations).

So what has not come true? In our 2023 review we noted that the UK “government has hinted that it might reverse PACCAR entirely (and so amend the [2013 Damages-Based Agreements (‘DBA’)] Regulations) at the first opportunity)”. However, as is further explained below, the new government under Keir Starmer has chosen to first review funding more generally.

We had also expected harmonisation at least within leading common law jurisdictions of the law in respect of arbitration and winding-up proceedings whereas the Privy Council decision in Sian Participation Corp (In Liquidation) v Halimeda International Ltd 2 came as a surprise given that the previous leading decision on the topic (Salford Estates (No 2) Ltd v Altomart Ltd 3) had stood since 2014 and a prevailing trend of decisions broadly favouring the approach taken in Salford Estates. Sian Participation has led to a harmonisation of the laws of England and Wales and the British Virgin Islands (and likely also the Cayman Islands and offshore jurisdictions) but means that there are still inconsistent decisions across key common law arbitration jurisdictions, most notably, Hong Kong and Singapore.

Commencing arbitration and arbitrability

Notice of arbitration

A Hong Kong judgment released in the summer of 2024 will likely be welcomed by sole arbitrators in the fairly common but awkward situation in which a respondent does not engage in arbitration proceedings. In such situations, as the below case illustrates, it helps if the arbitrator is very familiar with the arbitral process and meticulous (eg in carefully defining and monitoring how a respondent is to be notified).

Pan Ocean Container Suppliers Co Ltd v Spinnaker Equipment Services Inc 4 concerned an HKIAC award. The unsuccessful plaintiff (and non-responsive respondent in the arbitration) was a Mainland Chinese company engaged in the manufacture of marine cargo containers and the defendant (and claimant in the arbitration) was a Californian company engaged in the business of leasing and selling containers. The HKIAC arbitration clause was found in a Hong Kong law purchase agreement for the manufacture of containers.

The defendant had successfully applied for the arbitration to be conducted in accordance with the Expedited Procedure under article 42.1 of the 2018 HKIAC Administered Arbitration Rules (“2018 Rules”). A sole arbitrator was appointed and an award for over US$10 million was published granting the defendant liquidated damages and damages. Importantly, the plaintiff did not participate in the arbitration at all.

Afterwards, the plaintiff argued that it never received the award and only found out about it when it learned that its bank account was frozen by an order of the Ningbo Maritime Court in an enforcement action. It issued an originating summons (without a supporting affirmation) to set aside the award relying on four UNCITRAL Model Law grounds namely:

(1) article 34(2)(a)(ii) claiming it was not given proper notice of the appointment of the tribunal or of the arbitral proceedings or was otherwise unable to present its case;

(2) article 34(2)(a)(iii) claiming the award dealt with a dispute not contemplated by or falling within the terms of the submission to arbitration, or contains decisions on matters beyond the scope of the submission to arbitration;

(3) article 34(2)(a)(iv) arguing the composition of the tribunal or the arbitral procedure was not in accordance with the agreement of the parties; and

(4) article 34(2)(b)(ii) arguing that the award was in conflict with Hong Kong public policy.

Deputy High Court Judge Jonathan Wong in Chambers analysed the evidence in the context of the notification requirements under the applicable 2018 Rules and rejected all arguments. As to argument (1) upon characterising this argument was “entirely opportunistic”, the judge approvingly cited KB v S 5 as authority for the premise that:

“in dealing with applications to set aside an arbitral award, or to refuse enforcement of an award, whether on the ground of not having been given notice of the arbitral proceedings, inability to present one’s case, or that the composition of the tribunal or the arbitral procedure was not in accordance with the parties’ agreement, the court is concerned with the structural integrity of the arbitration proceedings. In this regard, the conduct complained of “must be serious, even egregious”, before the court would find that there was an error sufficiently serious so as to have undermined due process.”

There were several sub-arguments that fell under argument (2), all of which failed. The most interesting argument relates to the quantum of the claim (which topic we also discuss in our final section). In its notice of arbitration the defendant had requested:

“a direction pursuant to Article 42 that the arbitration be conducted in accordance with the Expedited Procedure … The amount in dispute … well below the monetary threshold of HKD 25m set by the HKIAC.6 It follows that the matter falls under Article 42.1(a).”

The plaintiff argued, without citing authority, that the defendant should have on at least two occasions informed HKIAC that the Expedited Procedure was no longer appropriate. The judge disagreed and held:7

“… even within the ‘streamlined’ Expedited Procedure, the Tribunal was meticulous and careful in the process, even disallowing substantial parts of the Defendant’s claim without any input by the Plaintiff. … this complaint does not come close to having the character of precipitating a substantial injustice which is shocking to the court’s conscience.”

A secondary argument related to the alleged adduction of without prejudice communication also did not persuade the judge who found:8

“the Tribunal is an experienced barrister and I have no doubt that she was able to put any reference to without prejudice communications out of her mind. In any event, as pointed out above, the Plaintiff has not adduced into evidence what it considers to be without prejudice material.”

Arguments 3 and 4 related to the tribunal’s invitation for further submissions from the parties in the event that she was not minded to grant declaratory relief (for specific performance) and eventually led to an additional significant head of claim being awarded. The plaintiff’s complaints in respect of these arguments were formulated in a number of different ways none of which succeeded.

The plaintiff was ordered to pay the defendant the costs of the originating summons application (and ancillary applications) on an indemnity basis.

As mentioned above, the judgment may be reassuring to arbitrators. In a situation where a respondent does not participate, the tribunal may need to make an impartial and independent assessment of all arguments and evidence presented by the participating party in order to satisfy themselves that the claims of the participating party are well founded in fact and in law9. This can, especially in complicated cases, lead to the claimant producing several consecutive rounds of submissions and evidence. The court also noted approvingly that the tribunal did not award exactly the relief sought:

“It is pertinent to note that, although the Plaintiff did not participate in the Arbitral Proceedings, the Tribunal disallowed two substantial claims made … Even in respect of the Non-Delivery Claim, the sum awarded was significantly less than that originally claimed by the Defendant, upon clarification requested by the Tribunal’s own initiation”.10

Is there a dispute? “It takes two to tango”

The Hong Kong Court of Appeal’s judgment in CMBICDHAW Investments Ltd v CDH Fund V Ltd Partnership and Others 11 has an amusing overture:

“It is well settled that it takes two to tango. The question which arises in this appeal is whether it also takes two to create a ‘dispute’, capable of giving jurisdiction to an arbitrator to resolve that dispute.”12

The short answer is: yes. As “has become the usual practice in the context of challenges to arbitration awards”13 in Hong Kong costs were awarded against the unsuccessful defendants on an indemnity basis.

The key facts were that there was an ICC arbitration agreement in an investment agreement (in a company specialised in Chinese meat production, sales and processing) made between three parties (Fund, Cattle and CMB). Fund and Cattle (plus three non-contracting parties) commenced arbitration claiming a declaration of non-liability to CMB. CMB, meanwhile asserted claims against the non-contracting parties in High Court litigation but never asserted any liability of Fund and Cattle (for which they sought the negative declaration of non-liability).

CMB objected to the jurisdiction of the arbitrator as regards: (1) Fund and Cattle’s claim, on the basis that there was no “dispute” to be resolved; and (2) as regards the non-contracting parties, on the basis that they were not parties to the arbitration agreement. The arbitrator declined to rule on jurisdiction as preliminary threshold question. While, in his final award, the arbitrator agreed that there was no jurisdiction over the claim asserted by the non-contracting parties, he decided that there was jurisdiction over the claim made by Fund and Cattle, and granted a declaration of non-liability. CMB then applied to court under section 81 of the Arbitration Ordinance (ie article 34 of the UNCITRAL Model Law) to set aside that part of the award (and some other paragraphs of it), on the basis that it was made without jurisdiction and/or was contrary to public policy.

The case was originally heard de novo as CMB v Fund and Others 14 before Mimmie Chan J. She pointed out the arbitrator’s apparent error – in conflating whether there is a dispute with whether there was a legitimate interest in seeking relief in the form of a negative declaration – and agreed that the arbitrator had no jurisdiction. The public policy point was not considered. Fund and Cattle then obtained leave to appeal and the Court of Appeal duly heard the appeal again approaching the jurisdiction question de novo: was there “a ‘dispute’ between Fund and Cattle on the one hand and CMB on the other – either at the time of the commencement of the arbitration and/or at the time the Arbitrator came to write his Award”?15

The Court of Appeal agreed with Mimmie Chan J that the arbitrator did not have jurisdiction having first summarised the applicable principles as follows:16

“(1) In the arbitration context, the term ‘dispute’ should be construed inclusively and not overly legalistically.

(2) For a ‘dispute’ to exist, it is unnecessary for there to be a ‘claim’ in the sense of a legal claim or legal cause of action asserted by one party against the other.

(3) Various phrases have been adopted in previous authorities to identify the sufficiency of existence of a ‘dispute’, such as ‘assertion or adoption of a position by one party which is expressly or by implication rejected or at least not accepted by the other’ and ‘a difference of opinion about the central issues’.

(4) Therefore, there must be something in the nature of an assertion by one party, and a situation in which the parties neither agree nor disagree about the true position is not one in which there is a dispute.

(5) Further, some cases identified that silence in the face of a claim or assertion does not raise a dispute, as what is required is a rebuttal or denial of the claim or assertion.

(6) The phrase ‘arising out of or relating to’ is to be given a broad construction, and ‘relating to’ has a wide meaning intended to convey some connection between two subject matters.

(7) The time for determining whether a ‘dispute’ has arisen is as at the time of the commencement of the arbitration, when the arbitrator’s jurisdiction is invoked, because it is the existence of the dispute which engages that jurisdiction.

(8) In other words, it must be possible to formulate the ‘dispute’ which is said to engage the jurisdiction.

(9) A ‘dispute’ may arise and continue to exist, unless there is a clear and unequivocal admission of both liability and quantum.”

In addition, the Court of Appeal considered: “the relevant parts of the Award in conflict with the public policy of Hong Kong”. While it accepted that the public policy ground in section 81/article 34(2)(b)(ii) of the Model Law is “not a ‘catch-all’ provision to be used whenever convenient” but rather is “limited in scope and sparingly applied” where there is “something which is contrary to fundamental conceptions of morality and justice”, the Court of Appeal was persuaded that there had been a conflict within the award with the public policy of Hong Kong, that would (in addition to the jurisdiction point) lead to the setting aside of the parts of the award set aside. It commented17:

“it is unfortunate that the Arbitrator – even after having recognised that he need not decide anything on the evidence – went on to give a declaration that the allegations made in the HCA were false, and further offered his ‘notes’ as potentially providing ‘some assistance in’ the HCA on the matters he thought not necessary for him to decide. With respect, that at least risked giving the impression that the Arbitrator was seeking to ‘poison the well’.”

Has the alternative dispute resolution mechanism clause been superseded?

Tyson International Co Ltd (“TICL”) is a captive insurer18 for Tyson (a multinational food company that processes, sells and markets meat) and was reinsured with various reinsurers including Partner Re and GIC. There was a fire and TICL paid claims whereas reinsurers resisted (eg GIC on the grounds of mis-representation and the rescission remedy). As a result, the English courts first had to consider interesting jurisdictional preludes.

In Tyson International Co Ltd v Partner Reinsurance Europe SE 19 Stephen Houseman KC sitting as judge in the High Court concluded that the dispute resolution provisions in the standard “Market Reform Contract” (“MRC”) (namely English law and the exclusive jurisdiction of the English court) were superseded by those contained in a subsequent document (“Facultative Certificate” or “Market Uniform Reinsurance Agreement”) which provided for New York law and arbitration issued eight days later. Accordingly, he granted a stay of the action begun by Tyson in the Commercial Court pursuant to section 9 of the Arbitration Act 1996 (and refused to grant an anti-arbitration injunction).

The Court of Appeal agreed:20 “… as Lewis LJ put it in argument, the parties began by playing cricket but then switched to baseball”.21

Similar questions arose in respect of reinsurance policies issued to TICL by GIC. But there was an important difference: in the GIC cases the conflicting documents also included the following clause “RI slip [ie, the Market Reform Contract] to take precedence over reinsurance certificate in case of confusion”. In Tyson International Co Ltd v GIC RE, India, Corporate Member Ltd,22 in considering whether it was appropriate to continue an interim anti-arbitration injunction restraining New York proceedings, Christopher Hancock KC sitting as High Court Judge continued an interim anti-arbitration injunction pending any application to be made by GIC challenging the jurisdiction of the English court, including any application made under section 9 of the Arbitration Act 1996. This was confirmed in a 2025 decision (by Mr Nigel Cooper KC sitting as High Court judge).23 Christopher Hancock KC had read the afore-cited clause as a “hierarchy clause” whereas in 2025 Mr Nigel Cooper KC preferred the term “confusion clause”. Mr Cooper KC considered that the term “confusion” encompasses both uncertainty and inconsistencies within the contractual terms.24 He found “that the Confusion Clause is to be construed as a clause which gives precedence to the terms of the MRC in the event that there is confusion or inconsistency between the terms of the MRCs and the terms of the Facultative Certificates”.25

While GIC tried to argue that that the two sets of dispute resolution provisions could be reconciled (either because one clause was a Scott v Avery clause or because the jurisdiction clause could be read as giving the English courts a supervisory jurisdiction in relation to the New York arbitration).26 Mr Cooper KC disagreed:

“… one can anticipate experienced insurance professionals such as the individuals working for GIC and TICL entering reinsurance contracts which provide either for dispute resolution under English law before the courts of England and Wales or dispute resolution under the law of New York before a New York arbitration tribunal with the New York courts having supervisory jurisdiction. What seems to me extremely unlikely is that such insurance professionals would agree that their disputes should be resolved by arbitration in New York with the courts of England and Wales exercising a supervisory jurisdiction and the courts of the United States also having a residual jurisdiction.”27

In Singapore, in CNA v CNB and Another 28 the appellant sought to set aside a partial award rendered by an ICC tribunal. CNA, contended partial awards should be set aside under article 34(2)(a)(i) (incapacity) and/or (ii) (notice) of the UNCITRAL Model Law, as enacted in the International Arbitration Act 1994 (2020 Rev Ed) arguing that the tribunal had no jurisdiction because the ICC Clause, which purportedly gave it jurisdiction, had been superseded by a SHIAC Clause. The original arbitration agreement, contained in a software licencing agreement, dated 2010 read:

“This Agreement shall be governed and construed by in accordance with the laws of Singapore. All disputes arising under this Agreement shall be submitted to final and binding arbitration. The arbitration shall be held in Singapore in accordance with the Rules of Arbitration of the International Chamber of Commerce.”

A 2017 extension agreement contained the following:

“Amendment to Disputes, Governing Law. The Original Software Licensing Agreement, each of the Amendments, and this Agreement shall be governed and construed by in accordance with the laws of People’s Republic of China. All disputes arising under either the Original Software Licensing Agreement, any of the Amendments or this Agreement shall be submitted to final and binding arbitration to Shanghai International Arbitration Centre (‘SHIAC’). The arbitration shall be held in Shanghai, PRC in accordance with the Rules of SHIAC.”

The Court of Appeal rejected the appeal effectively for two reasons. The first had to do with whether CNA had validly entered into the extension agreement. It found CNA was in breach of fiduciary duty (arising out of the contractual matrix) to CNB in entering into the 2017 extension agreement. Secondly it noted that the ICC arbitration had already been commenced when the 2017 extension agreement was executed and suggested that:

“The haste and secrecy with which CNA acted in entering into the 2017 Extension Agreement in the circumstances found by the SICC indicated a purpose of supporting a jurisdictional objection to the 2017 ICC Arbitration.”29

The Court of Appeal found:30

“As a matter of construction, the language of the dispute resolution clause in the 2017 Extension Agreement was not apt to remove the jurisdictional foundation previously agreed in the SLA between the parties to the 2017 ICC Arbitration. To affect an arbitration that was already afoot, cl 2 would have needed to be explicit in its terms; but that plainly was not done, presumably because it would have shone the light on precisely what CNA was trying to do – namely to fabricate a jurisdictional objection. Hence, for this reason also, even if it had not breached its fiduciary obligations to CNB, CNA could not have succeeded on the jurisdictional challenge based on the new dispute resolution provision.”

Who decides – the tribunal or the court?

Normally a tribunal rules on its own jurisdiction (eg under Kompetenz-Kompetenz). For example, section 30 of the English Arbitration Act 1996 enables the tribunal to determine its own jurisdiction subject to the right of a party to challenge such a decision under section 67. Section 32 contains a derogation and reads:

“32 Determination of preliminary point of jurisdiction.

(1) The court may, on the application of a party to arbitral proceedings (upon notice to the other parties), determine any question as to the substantive jurisdiction of the tribunal. A party may lose the right to object (see section 73).

(2) An application under this section shall not be considered unless—

(a) it is made with the agreement in writing of all the other parties to the proceedings, or

(b) it is made with the permission of the tribunal and the court is satisfied—

(i) that the determination of the question is likely to produce substantial savings in costs,

(ii) that the application was made without delay, and

(iii) that there is good reason why the matter should be decided by the court.”

In Barclays Bank plc v VEB.RF,31 in a dispute between a UK and a Russian bank in relation to ISDA currency swaps impacted by sanctions, the Commercial Court concluded that it could exercise its rarely invoked power under section 32 to determine the jurisdiction of an LCIA sole arbitrator (a sole King’s Counsel).

While the arbitrator had granted permission, the court nonetheless also had to apply the above test:

“… the court is not a rubber stamp of approval for the arbitrator’s decision. Even where permission is given, the judge will examine the issue afresh giving such weight to the arbitrator’s decision as the judge considers appropriate in the circumstances. If an arbitrator has been too easily persuaded on the cost issue, for example, it is highly unlikely that would influence the judge to reach a similar conclusion, quite simply because the judge approaches the issue afresh.”32

As regards the applicable principles, obiter comments in Armada Ship Management (S) Pte Ltd v Schiste Oil and Gas Nigeria Ltd,33 a judgment on a paper application with submissions from only one party, were considered helpful (albeit non-binding):

“The fundamental point that emerges from this authority and those referred to in it is that whether the statutory criteria set out in section 32(2) are satisfied is a fact-sensitive question which has to be resolved by reference to the particular facts of each and every case where the question arises.”34

On the facts, the judge independently agreed that the court should decide jurisdiction:

“… disposing of the jurisdiction issue now provides finality, eliminates substantial additional costs, eliminates the risk of costly and time-consuming issues on enforcement, and delivers substantial content to the contractual obligation concerning exceptional urgency. Given my conclusions, the conclusion of the tribunal to similar effect in the particular circumstances of this case add nothing to the conclusions I have already reached.”35

The virtual certainty of a section 67 appeal was (as we discuss further below) an important factor.

Scope of arbitration clauses – can tort claims be covered?

The Singapore Court of Appeal in COSCO Shipping Specialized Carriers Ltd v PT OKI Pulp & Paper Mills and Others 36 contains helpful analysis on how to approach this question and how to apply the “closely knitted test”. The issue that arose is that a trestle bridge was damaged by the vessel (an allision) causing significant loss to the bridge owner which issued proceedings in Indonesia. The arbitration was brought under contracts of carriage (namely bills of lading issued to the shipper) that were issued in the context of the vessel having been chartered to a charterer and sub-chartered (to the Indonesian company which owned the mill). As a matter of law, the relevant dispute resolution clause was incorporated (into the bill of lading) by reference from the head charterparty. It provided for “any dispute arising out of or in connection with this Contract” to be referred to SIAC arbitration. The question was whether tort claims were covered and whether the Singapore court could issue an anti-suit injunction to restrain the Indonesian proceedings. The High Court said no; the Court of Appeal said yes.

The Court of Appeal’s view of the case was that:

“… it was evident that the tortious claim, the contractual defence of negligent navigation and the cross-claim for breach of the Safe Port Warranty all shared a common connection – namely, what was the cause of the allision? The answer to that common question had a direct impact on the competing claims and defence.”37

It was not relevant to ask – as had the High Court judge – whether the claim was causally connected to the legal relationship under the bills of lading:

“The ‘connection’ inquiry required an examination of the nature of the tortious claim in tandem with the contractual defence and not the contracting capacities of the parties. The fact that [OKI’s] was brought in its capacity as a jetty owner and not as a shipper did not change the fact that the allision occurred in the performance of the contract of carriage which also provided for the contractual defence of ‘errors of navigation’.”38

Pathological clauses – are they salvageable?

Unfortunately, dispute resolution clauses (including arbitration clauses) are often “midnight clauses” which often causes problems. The term pathological clause (or clause pathologique) was first coined by Frédéric Eisemann, a former Secretary-General of the ICC Court of Arbitration, in 1974 to describe arbitration clauses that fail to achieve their object. As the following case illustrates, in pro-arbitration jurisdictions like Hong Kong, England and Singapore, the courts tend to do their best to uphold imperfect arbitration clauses.

In Tongcheng Travel Holdings Ltd v OOO Securities (HK) Group Ltd and Another,39 Mimmie Chan J again considered what happens if the chosen arbitration institution does not exist or has ceased to exist. The defendant had applied to set aside a default judgment (and garnishee order to show cause) against it and to stay the proceedings to arbitration under section 20 of the Arbitration Ordinance. The stay application was determined first (in the defendant’s favour in spite of the delay). The context was a Chinese language investment management agreement whereby the defendant was to manage the investments of the plaintiff (of approximately US$30 million) and which provided inter alia (as translated):

“11.2 The courts of Hong Kong shall have exclusive jurisdiction over the parties to this Agreement.

11.3 Any and all dispute(s) arising out of or in connection with this agreement shall be resolved by friendly negotiations between the parties insofar as possible. Both parties agree to negotiate in good faith to resolve any dispute(s). If, within 7 days of one party notifying the other of any dispute(s), the parties fail to resolve any such dispute(s), the dispute(s) shall be submitted to the relevant legally authorised body in Hong Kong for arbitration in accordance with the arbitration rules presently in force at the time of submission to arbitration. The place of arbitration shall be Hong Kong and the language for arbitration shall be Chinese or English. The arbitral award is final and binding on both parties. During the period of dispute resolution, the parties shall continue to perform this agreement save for the disputed matters.”

The court resolved the case having approvingly cited her previous case: Chimbusco International Petroleum (Singapore) Pte Ltd v Fully Best Trading Ltd:40

“Lucky-Goldstar International (HK) Ltd v Ng Moo Kee Engineering Ltd [1993] 1 HKC 404 is clear authority that where the parties have clearly expressed an intention to arbitrate, the agreement is not nullified even if they chose the rules of a non-existent organizations. In the present case, the parties expressed the manifestly clear intention to have the dispute submitted to arbitration in Singapore. Such agreement is capable of being performed in Singapore, and it is for the tribunal to decide on its own jurisdiction, and on the rules to be adopted. If necessary, the parties can apply to the Singapore court to appoint the arbitrator(s).”

Exclusive jurisdiction clauses (in addition to arbitration clauses)

In Tongcheng Travel Holdings Ltd v OOO Securities (HK) Group Ltd and Another 41 (which we have discussed above) the court also held that the conflict between clauses 11.2 and 11.3 (see above) was not irreconcilable:

“Whereas clause 11.3 is an expression of the parties’ intention to refer disputes to arbitration in Hong Kong, article 11.2 in providing for the parties’ submission to the exclusive jurisdiction of the Hong Kong courts can be reconciled to mean that the Hong Kong court is to have supervisory jurisdiction over the arbitration in Hong Kong.”42

The court reached this conclusion having discussed several decided Hong Kong and English law cases as authority: Lee Cheong Construction & Building Materials Ltd v Incorporated Owners of The Arcadia (IO);43 Paul Smith Ltd v H&S International Holding Inc;44 Sul América Cia Nacional de Seguros SA v Enesa Engenharia SA;45 Arta Properties Ltd v Li Fu Yat Tso;46 Bluegold Investments Holdings Ltd v Kwan Chun Fun Calvin;47 and Neo Intelligence Holdings Ltd v Giant Crown Industries Ltd.48

Readers may note that a similar argument failed in Tyson International Co Ltd v GIC RE, India, Corporate Member Ltd 49 (discussed above) where GIC unsucessfully argued that the English court could supervise a New York seated arbitration (ie in a different jurisdiction) and where there was also a hierarchy clause.

Multiple party/multiple contract arbitrations

Multi-party arbitration involves more than two parties. In multi-contract arbitration the dispute arises out of two or more contracts which are connected to varying degrees, and there are arbitrations which are both multi-party and multi-contract.50 It is often cheaper and faster for claims to be heard as one. That way awards should be consistent.

However, multiple related contracts with conflicting dispute resolution clauses risk instead causing increased costs, delays and inconsistent awards/judgments. Parties should carefully think through how dispute resolution clauses work – which is not necessarily straightforward if more than two parties are involved:

“Courts and arbitral tribunals, in absence of an agreement of the parties to that effect will generally refuse to unify in one proceeding under one arbitration clause all the disputes arising under various agreements, when they contain truly incompatible arbitration clauses or jurisdictional clauses unless it undoubtedly appears that all the disputes fall within the scope of the relevant arbitration clause.”

Helpfully, the HKIAC has on 20 January 2025 issued a Practice Note on Compatibility of Arbitration Clauses under the HKIAC Administered Arbitration Rules51by way of non-binding guidance on how the HKIAC generally applies articles 28.1(c) and 29 in practice. Paragraph 3.1 thereof is surprisingly simple:

“Where a transaction involves more than one contract, parties are advised to use HKIAC’s model arbitration clause in each contract and to provide for the same seat, number of arbitrators, law governing the arbitration agreement and language of the arbitration in each clause. Using HKIAC’s model arbitration clause will maximise the chances that the clauses will be compatible.”52

Below we set out some examples of the kinds of problems conflicting dispute resolution clauses caused just in 2024 which we imagine inspired the HKIAC to issue its guidance. By way of context, article 29 of the 2018 HKIAC Administered Arbitration Rules reads:

“Claims arising out of or in connection with more than one contract may be made in a single arbitration, provided that:

(a) a common question of law or fact arises under each arbitration agreement giving rise to the arbitration; and

(b) the rights to relief claimed are in respect of, or arise out of, the same transaction or a series of related transactions; and

(c) the arbitration agreements under which those claims are made are compatible.”

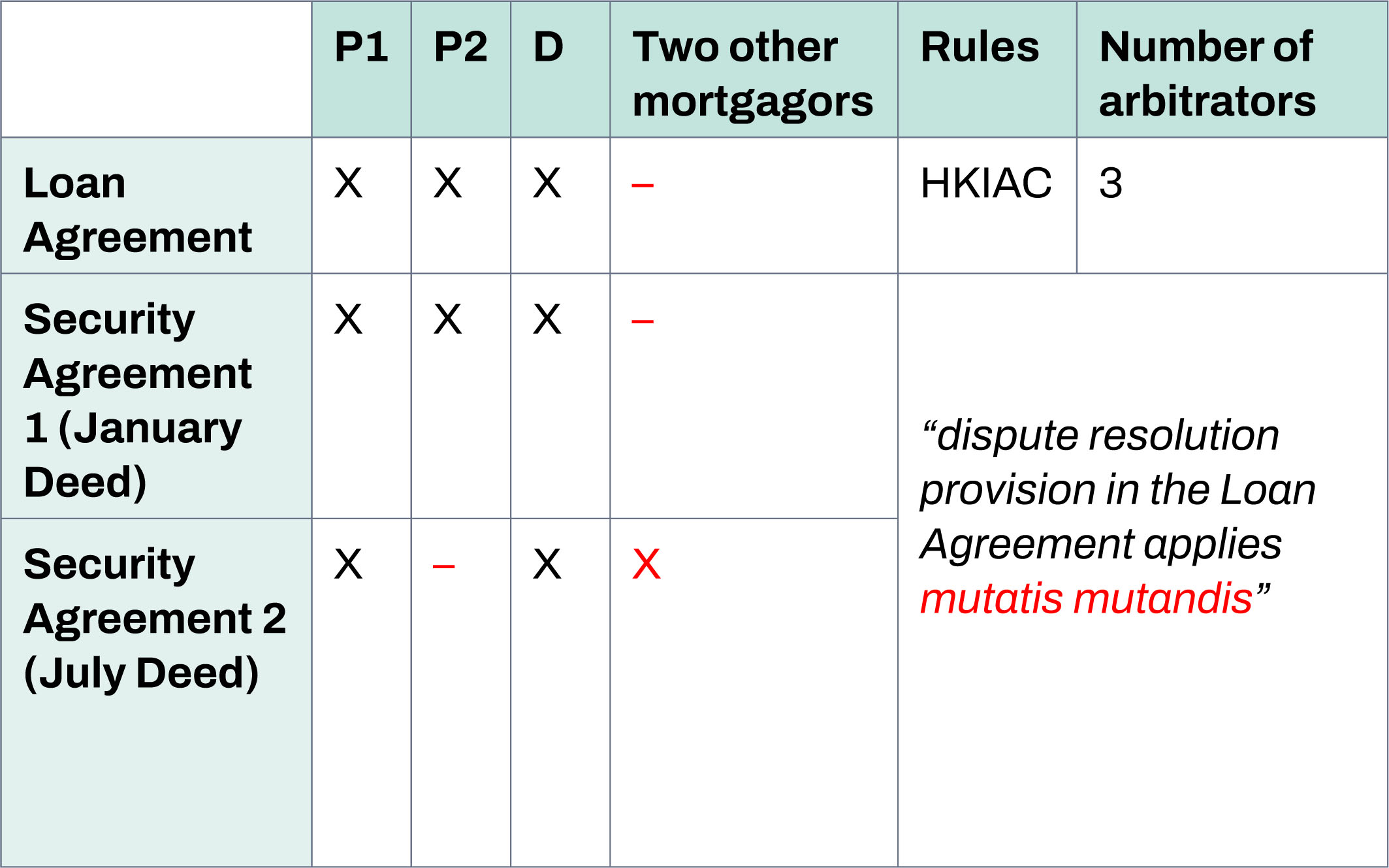

In SYL and Another v GIF,53 in the context of an application to set aside an interim arbitral award, the Hong Kong court had to consider where three agreements were compatible. The problem can be described in a table:

The dispute resolution clause in the Loan Agreement read:

“Each of the parties hereto irrevocably … agrees that any dispute or controversy arising out of, relating to, or concerning any interpretation, construction, performance or breach of this Agreement, shall be settled by arbitration to be held in Hong Kong which shall be administered by the Hong Kong International Arbitration Centre (‘HKIAC’) in accordance with the Hong Kong International Arbitration Centre Administered Arbitration Rules … There shall be three (3) arbitrators, with one arbitrator to be appointed by the Borrowers and one arbitrator to be appointed by the Lender. If the aforesaid two arbitrators fails to agree on the third arbitrator, the HKIAC Council shall select the third arbitrator, who shall be qualified to practice law in Hong Kong …”

The issue that arose is that the appointment mechanism did not work: three arbitrators had to be appointed whereas in all agreements the parties acted in different capacities (hence the need to work out what “mutatis mutandis” meant) and – another complication – Security Agreement 2 had different parties. The judge found as follows:

“there is a clash in the appointment procedure in the Loan Agreement and the January Deed on the one hand, and the July Deed on the other hand:

(1) Under the Loan Agreement and the January Deed, Ps would have the right to designate an arbitrator. The Other Mortgagors have no say.

(2) However, under the July Deed, it is P1 and the Other Mortgagors who would have the right to designate an arbitrator. P2 has no say.”54

The judge found that since the three agreements “provide for different appointment procedures, the Arbitration Agreements are not compatible with each other”,55 and set aside the interim award. He came to the conclusion on the basis that consolidation infringes party autonomy (and party consent); infringes the parties’ contractual rights and there are valid concerns over whether D may gain an unfair advantage in the arbitration by refusing Ps a right to designate an arbitrator of Ps’ choice.

It is worth underlining that the case related to 2018 Rules. As we further discuss below, new Administered Arbitration Rules were released by the HKIAC in 2024 which inter alia contain the below additional subsection to article 29:

“29.2 Where HKIAC decides pursuant to Article 19.5 that the arbitration has been properly commenced under this Article 29, the parties shall be deemed to have waived their rights to designate an arbitrator. HKIAC shall appoint the arbitral tribunal with or without regard to any party’s designation.”

It is possible, however, that the above new provision would not solve the problem. In particular, it has already been argued56that compatibility of the arbitration agreements remains a threshold issue which must be satisfied in order for a single arbitration under multiple contracts to have been validly commenced in the first place. (The relevant section of the rules, as renumbered article 29(1)(c) remains unchanged.)

In AAA and Others v DDD 57 the Hong Kong Court of First Instance set aside an arbitral tribunal’s decision on jurisdiction. The context was a dispute triggered by borrower default. The court found that the tribunal had incorrectly assumed jurisdiction over disputes related to a Promissory Note despite conflicting arbitration clauses in related contracts including:

- • Loan agreement (between lender; borrower; and guarantors) subject to HKIAC arbitration with a three-arbitrator tribunal.

- • Promissory note (issued by the borrower to the lender; signed by borrower and guarantors) also subject to HKIAC arbitration but without specifying the number of arbitrators.

- • Amendment agreement to the loan agreement which incorporated the arbitration clause of the loan agreement.

Before reaching its decision, the court (Anselmo Reyes SC) tried – unsuccessfully – to reconcile inconsistent arbitration clauses applying the “centre of gravity” approach (Trust Risk Group SpA v AmTrust Europe Ltd58) which we further discuss below.

The Singapore decision of Sacofa Sdn Bhd v Super Sea Cable Networks Pte Ltd and Another 59 raised a number of issues on the interpretation of an arbitration clause where there had been a partial carve out of issues under a separate agreement (a lease). The court’s approach to the question whether a decision of an enforcing court had preclusive effect where a later challenge to the award was made in the curial court is also interesting.

Sacofa was a Malaysian telecommunications infrastructure supplier which operated a cable landing station. Sacofa and Super Sea entered into a Strategic Alliance Agreement (SSA) to build and operate various facilities including on the landing station. The SSA contained an arbitration clause providing for SIAC arbitration “for a dispute (of any kind whatsoever) [arising] between the Parties in connection with, or arising out of, the Agreement or the performance of the obligations of the Parties”. SEAX Malaysia Sdn Bhd (R2) was not a party to the SSA, but was nominated as the licensee to which the built facilities would be transferred under the SSA. Per the SSA, Sacoma leased a part of its land to Super Sea, the lease providing for disputes to be subject to the exclusive jurisdiction of the Malaysian courts in respect of “validity, construction and performances” under the lease. The relationship soured when the claimant re-entered the land on which the system was to be built. The claimant claimed that Super Sea did not have the requisite regulatory licences to undertake the project and sued before the Malaysian courts.

The Malaysian court refused Super Sea and R2’s application to stay in favour of arbitration on the ground that the dispute arose under the lease. Super Sea and R2 commenced arbitration against under the SSA (in conversion). The tribunal ruled that it had no jurisdiction over R2 because it was not a party to the arbitration clause, but held that Super Sea was entitled to an order requiring the delivery up of the built facilities to R2. Sacofa applied to the Malaysian court for an anti-arbitration injunction pending the resolution of the proceedings in Malaysia, arguing that the issues submitted to arbitration overlapped with those before the court. That application was dismissed without written reasons, as was an appeal. A month later Super Sea was granted an order from the Kuala Lumpur High Court registering and enforcing the award. Sacofa appealed, and failed – pending the appeal – to obtain a stay of enforcement.

The Singapore High Court refused to set aside the SIAC award. The set-aside application was based on two arguments: (i) that the tribunal had exceeded its jurisdiction; and (ii) that the award violated the governing Malaysian law, which was contrary to Malaysia’s public policy and in turn also contrary to Singapore’s public policy.

The Singapore court considered and answered three questions as follows.

(1) Whether the “centre of gravity” of the claim for conversion lay in the SAA or the lease; whether the claim for conversion was inextricably linked to the lease (and cannot arise solely from the SAA), and; whether the remedy of delivery-up was within the tribunal’s jurisdiction

Where a dispute potentially falls within the ambit of either dispute resolution clause the test is which dispute resolution clause the parties objectively intended to apply. To determine this, the court must locate the “centre of gravity of the dispute” or the “pith and substance of the dispute as it appears from the circumstances in evidence” (Oei Hong Leong v Goldman Sachs International 60). The court held that the centre of gravity of the claim for conversion lay in the SAA. The claim for conversion and the consequential relief of delivery-up arose out of the SAA, and hence was within the tribunal’s jurisdiction.

(2) Whether the award was in furtherance of an illegal act under Malaysian law and hence against the public policy of Singapore, and whether the doctrine of res judicata applied to estop the claimant from raising its illegality objections

There was no evidence of an illegal act under Malaysian law:

“The issue of foreign public policy is not a matter that Singapore courts can decide of its own accord and without evidence. On the latter, even if the Award were contrary to Malaysian public policy, it is trite law that the Public Policy Ground is only satisfied in exceptional circumstances.

…

The extended doctrine of res judicata operates to estop a party from raising matters that (a) are covered by an arbitration agreement, (b) are arbitrable, and (c) could and should have been raised by one of the parties in an earlier set of proceedings that had already been concluded (AKN and Another v ALC and Others and other appeals [2016] 1 SLR 966 at [59]). Only the last element was disputed.”61

The court found “the claimant could have raised the issue of illegality in the Arbitration but did not do so”.62

Thus that even if the award fell under the Public Policy Ground, the claimant was estopped from raising its illegality objections to set aside the award.

(3) Under the doctrine of transnational issue estoppel, whether the claimant was estopped from raising its jurisdictional and/or illegality objections

The Court of Appeal in Republic of India v Deutsche Telekom AG 63 dealt with this doctrine in the context where an issue decided by a seat court was subsequently raised before the Singapore enforcement court. In that case the Court of Appeal also expressed a view on the reverse situation:

“… We only observe that if the position to be taken is that transnational issue estoppel does apply in the context of international arbitration, then any departure from that position when considering a prior decision of an enforcement court would have to be grounded in principle, and that may, or may not, lie in the policy that is reflected in the scheme for the judicial supervision and support of arbitral proceedings, which does place an emphasis on the seat court, and for the recognition and enforcement of awards.”64

The court found:

“A distinction should be drawn between objections that specifically implicate the enforcement jurisdiction’s own statutes, public policy and other domestic interests (eg, the alleged contravention of the CMA), and objections that do not (eg, the interpretation of the SAA and the LA). While the principle of comity has a greater weight in relation to the former type of objections, the principle of party autonomy should be upheld in relation to the latter. To explain, the parties’ choice of seat entails an implicit agreement to favour the supervisory jurisdiction of the seat court over the jurisdiction of the other enforcement courts (see Sundaresh Menon CJ, ‘The Role of the National Courts of the Seat in International Arbitration’, keynote address at the 10th Annual International Conference of the Nani Palkhivala Arbitration Centre (17 February 2018) at para 53). Hence, it is the seat court which ought to have a final say on that litigated objection. In this case, the claimant’s jurisdictional objections were of a different nature from the illegality objections founded upon Malaysian law and public policy. Accordingly, I found that transnational issue estoppel should not apply to the claimant’s objection that the Tribunal acted in excess of his jurisdiction.”65

As we have seen in our above section (“Who are the parties”), where there are multiple contracts or parties, there is a risk that courts and tribunals reach inconsistent conclusions.

Court-mandated alternative dispute resolution

In Halsey v Milton Keynes General NHS Trust 66 Dyson LJ said that: “to oblige truly unwilling parties to refer their disputes to mediation would be to impose an unacceptable obstruction on their right of access to the court”. In 2024 the court had a chance to reconsider this. In November 2023, in Churchill v Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council,67 the English Court of Appeal held that a court can lawfully order the parties to court proceedings to engage in a non-court-based dispute resolution process (also known as alternative dispute resolution) provided that the order does not impair the essence of the claimant’s right to a judicial hearing, and it is proportionate to achieving the legitimate aim of settling the dispute fairly, quickly and at reasonable cost. However, the judge did:

“not believe that the court can or should lay down fixed principles as to what will be relevant to determining those questions. The matters mentioned by the Bar Council and Mr Churchill, and by the Court of Appeal in Halsey are likely to have some relevance. But other factors too may be relevant depending on all the circumstances. It would be undesirable to provide a checklist or a score sheet for judges to operate. They will be well qualified to decide whether a particular process is or is not likely or appropriate for the purpose of achieving the important objective of bringing about a fair, speedy and cost-effective solution to the dispute and the proceedings, in accordance with the overriding objective.”68

Halsey, which was viewed by many as a thorn in the side of mediation, was thus overruled. Unsurprisingly, Churchill led to a review of the Civil Procedure Rules (CPR) (which we discuss in the final “Trends” section under “Mediation”) and it is looking likely that mediation will become more firmly integrated into the civil justice system.

While it is true that attempts to mandate parties to mediate can be counterproductive, prompts to consider ADR (that come to the attention of parties’ C-suites) can be helpful. Similarly, it is helpful that the relatively young Singapore Convention on Mediation, which provides a harmonised framework for the enforcement and invocation of international settlement agreements resulting from mediation, is quickly being signed and coming into force in more and more countries.69

Who are the parties?

The question of who the parties to an arbitration agreement can be complex especially in an international context.

“Arbitration is based on consent, generally express consent. Is it therefore possible for somebody that is not formally identified as a party in the contract containing the arbitration agreement (a non-signatory) to be still considered a part to it? We will see that it is possible by application of theories such as agency and representation, third party beneficiary, incorporation by reference, universal or individual transfer, estoppel, implied consent, community of rights and obligations, alter ego, piercing the corporate veil and also implied consent.”70

Veil piercing and estoppel are theories often applied in the United States. Under English law (and Hong Kong and Singapore law) generally the doctrine of privity of contract applies. There, traditionally the parole evidence rule limits the ability to adduce of evidence on the intention of the parties. This makes it more difficult to apply the theory which Professor Hanatiau prefers to call “consent by conduct” or “implied consent” which has also been described as group of companies theory (applied for example in the United States, Canada, France, Switzerland, India, the Philippines and Bahrain).71 Professor Hanotiau also notes that some civil law countries (eg Germany, Holland, Russia and the PRC) are more restrictive; with Germany and Holland for example considering that consent always has to be certain and thus cannot be implied from conduct.

In 2024 we noted the following cases on these subjects:

- • In deciding an application seeking appointment of an arbitrator, the Indian Supreme Court gave a judgment clarifying the group of companies and composite transaction doctrines in Ajay Madhusudan Patel and Others v Jyotrindra S Patel and Others.72 While SRG Group was not a signatory to a family arrangement agreement, the successful petitioner argued that SRG’s active participation in negotiations and discussions on implementation made it a party to the arbitration agreement.

- • In Lakah et al v UBS AG et al,73 an attempt by Egyptian businessman Michel Lakah to set aside a 2018 ICDR award was rejected by the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York confirming its “strong presumption in favor of enforcing an arbitration award”. The outcome also confirms New York corporate veil piercing laws can be applied by both arbitral tribunals and the courts to parties in New York arbitrations to bind individuals personally to an arbitration agreement, regardless of whether the individuals involved are foreign or domestic.74

- • There have also been a couple of cases in England and Singapore in the context of anti-arbitration disputes which we discuss below including: Renaissance Securities (Cyprus) Ltd v ILLC Chlodwig Enterprises and Others,75 London Steam-Ship Owners’ Mutual Insurance Association Ltd v Trico Maritime (Pvt) Ltd and Others 76 and Asiana Airlines Inc v Gate Gourmet Korea Co Ltd and Others.77

Is the tribunal functus officio?

According to the traditional doctrine of functus officio, once a tribunal has issued its final award, its authority lapses. To allow de minimis changes nonetheless to be made to final awards, most arbitration laws and rules specifically contemplate the possibility of a party asking that the tribunal (in a limited way) correct, interpret, or supplement a rendered award (slip rule). Section 43 of Singapore’s Arbitration Act prescribes three situations such namely: (a) to correct arithmetical mistakes in calculation or typographical errors in the award; (b) to provide interpretation on a specific point or portion of an award so as to provide greater clarity; or (c) to make an additional award dealing with claims which were presented during the arbitral proceedings, but which were omitted for some reason from the actual award.

In Voltas Ltd v York International Pte Ltd,78 a major correction was requested after a final award had been issued. However, the Singapore Court of Appeal upheld the ruling of the High Court that an award made conditional on payment of damages by the award creditor to a third party was a final award and also not one that could be referred back to the arbitrator if there had been a dispute as to the amount paid.

In 2014 a sole arbitrator issued an award allowing some of the claims and counterclaims. However, the arbitrator noted Voltas had not actually paid certain sums claimed and might obtain a windfall if no payment was made. He discussed a legal authority79 that held that, if a windfall is possible, it is open to a tribunal to adjourn the decision quantum or to make a quantum award on condition that money is paid. The arbitrator chose the latter option and made his orders conditional on Voltas actually making the payment, the amount of liability being capped at the amount paid. Thereupon York refused to pay because Voltas had not provided sufficient evidence that it had indeed paid.

Thus, Voltas applied to the arbitrator for a further award, to determine whether payment had been made and issued a fresh notice of arbitration claiming payment. York objected on the basis that: disputes in the notice of arbitration did not fall within terms of the arbitration agreement; and that the arbitrator had issued a final award and was functus officio. The arbitrator, however, issued a written ruling concluding that he had jurisdiction to make a further award: although there was no express reservation, it was nevertheless implicit. York commenced the proceedings seeking an order to the effect that the arbitrator was functus officio.

Both the High Court and the Court of Appeal agreed with York. The Court of Appeal confirmed that tribunal loses its jurisdiction to reconsider the merits of the parties’ dispute, once it renders an award determining the issues. The award “was a final award in the third sense of PT Perusahaan. There was no substantive matter that was left undecided”.80 An implied reservation of jurisdiction is inconsistent with (article 43(4) of) the Arbitration Act.

Tribunals that would like to leave some matters (eg interest, costs or sanctions for failure to comply with an order) to be resolved by a subsequent award need to make expressly reservations (eg by designating the award as a “partial award” or adding a reservation to the operative part of the award).

Winding-up proceedings

As we discussed in our last review, when pursuing a straightforward commercial debt from a recalcitrant debtor, a creditor has two main options:

(1) commencing traditional proceedings and obtaining a judgment or an arbitration award (depending on the chosen forum in the contract) and then taking steps to enforce it via the courts against the debtor’s assets, or;

(2) issuing a statutory demand and then (if unpaid), petitioning to wind up the debtor.

Winding up is a collective remedy for the benefit of all creditors, and absent special circumstances, it is the end of a company. When wound up, or liquidated, professional insolvency practitioners (usually specialist accountants) will take control of the company, collect in its assets, and pursue claims, as appropriate, on the company’s behalf.

Ultimately, the liquidators, after deducting costs and certain statutory preferential payments, will distribute the company’s assets pari passu (proportionately) among creditors according to their claims. Because of the severity of winding up, often the threat of insolvency proceedings (ie the sending of a statutory demand) can bring a recalcitrant debtor to the negotiating table quickly and cheaply.

Contested winding up and arbitration

Prior to 2024, the leading decision regarding this topic (at least with respect to the law of England and Wales) was the Court of Appeal’s decision Salford Estates (No 2) Ltd v Altomart Ltd.81 In this case, the Court of Appeal held that if the debt in question was subject to an arbitration agreement and was disputed (or even “not admitted”) then, save for in “wholly exceptional circumstances” any winding up-petition should be stayed. The court expressed concern that to hold otherwise would encourage parties to an arbitration agreement, as a “standard tactic”, to bypass the arbitration agreement (and the intention of the Arbitration Act 1996) by presenting a winding up-petition to apply pressure on the alleged debtor. The approach set out and endorsed in Salford Estates was said to have represented a “new approach” whereby the parties are tightly held to the bargain laid out in the applicable arbitration agreement. This approach was generally viewed as being “pro-arbitration” as, while recognising the mandatory stay provisions were not triggered by the presentation of a winding-up petition, unless exceptional circumstances existed, required the court to exercise its discretion to stay the winding-up petition.

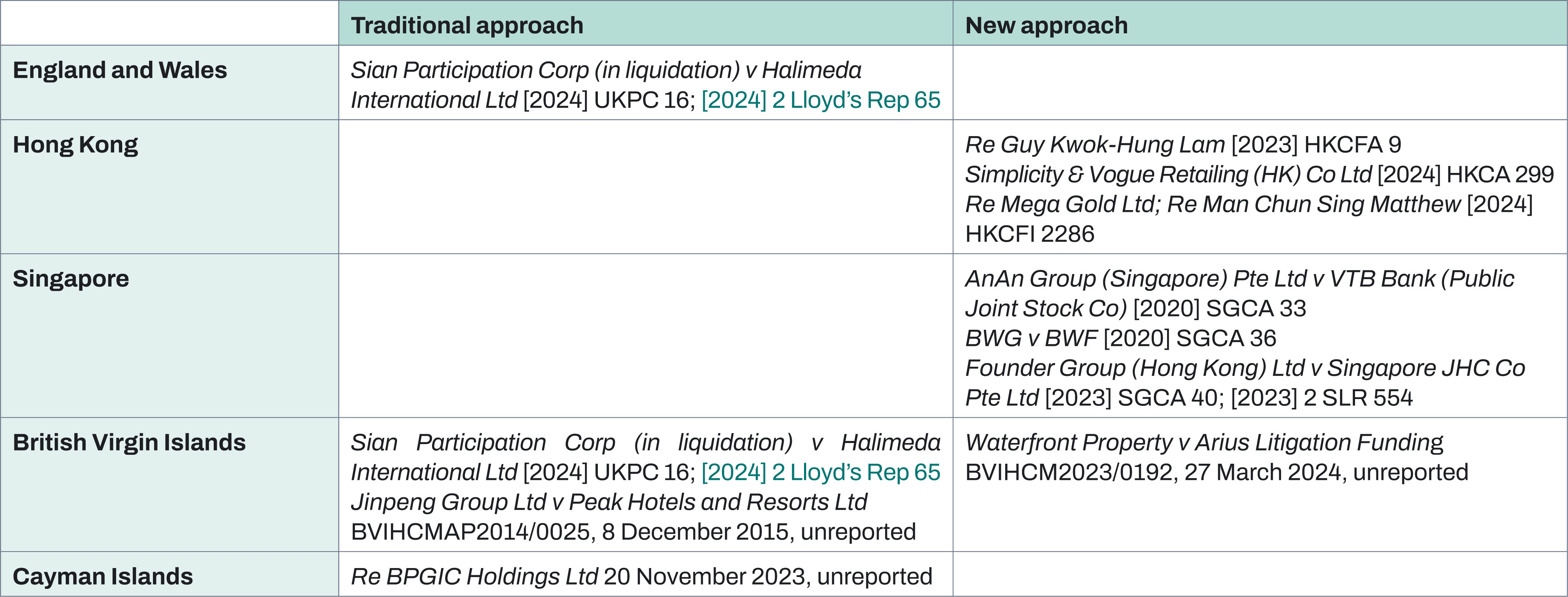

However, in Sian Participation Corp (in liquidation) v Halimeda International Ltd,82 the Privy Council decided that Salford Estates was wrongly decided. Although the decision concerned the law of the British Virgin Islands, the Board issued a Willers v Joyce direction83 to the effect that the decision in Sian Participation represents the law of England and Wales. The case concerned a US$226 million debt which, although denied by the company, was found not to be genuinely disputed. The Board held that:

“… the correct test for the court to apply to the exercise of its discretion whether to make an order for the liquidation of a company where the debt on which the application is based is subject to an arbitration agreement or an exclusive jurisdiction clause and is said to be disputed is whether the debt is disputed on genuine and substantial grounds.”84

In rejecting the approach endorsed in Salford Estates and reverting to the previously endorsed traditional approach, the Privy Council reasoned:

- • that the negative covenant embodied in an arbitration agreement not to commence proceedings outside the arbitration agreement is not offended by the presentation of a winding-up petition;

- • the pro-arbitration policies of the Model Law and the legislation enacting it are not infringed by a party to an arbitration agreement seeking to liquidate a debtor which fails to pay a debt; and

- • “The clearest legislative signal about the boundary of the policy that a party to an arbitration agreement should arbitrate is the extent of the mandatory stay provision which implements art 8 of the Model Law … A winding-up petition or similar application lies outside both that boundary and therefore the extent of the underlying policy.”85

As explained further below, the rejection of the approach taken in Salford Estates means that there is a clear divergence between the courts of England and Wales, the British Virgin Islands and the Cayman Islands who favour the traditional approach and the courts of Hong Kong and Singapore, on the other, which have deviated from the traditional approach. Below we update the table we published last year.

Hong Kong

In our last review we noted that there was no Court of Appeal authority on this point yet. There now is: In Simplicity & Vogue Retailing (HK) Co Ltd 86 the Court of Appeal upheld the discretion to wind up a company despite an arbitration clause. In so doing it confirmed that the principles regarding exclusive jurisdiction clauses laid down in the landmark decision by the Court of Final Appeal in Re Guy Kwok-Hung Lam 87 also apply to arbitration clauses.

After the Privy Council decision in Sian Participation (which we discuss above), in Re Mega Gold Ltd; Re Man Chun Sing Matthew 88 (heard together), the Hong Kong Court of First Instance held that it would nonetheless follow the Hong Kong approach as established in the Court of Final Appeal decision in Re Guy Kwok-Hung Lam and the Court of Appeal decision in Simplicity & Vogue Retailing as a matter of stare decisis.

Singapore

The High Court of Singapore commented on the contrasting positions of the English courts (as set out in the decision in Sian Participation) and the Singaporean courts (as set out in the decisions in AnAn Group (Singapore) Pte Ltd v VTB Bank (Public Joint Stock Co) and Founder Group (Hong Kong) Ltd v Singapore JHC Co Pte Ltd) in the decision in Re Sapura Fabricaiton Sdn Bhd.89 Here the Abdullah J noted the contrasting positions between the two jurisdictions, observed that he was bound by the decisions in AnAn and Founder Group (which followed Salford Estates) but ultimately concluded that it was not necessary to resolve the matter in the case which was before him.

British Virgin Islands

Prior to the decision in Sian Participation, the leading BVI decision regarding this issue was the Eastern Caribbean Supreme Court of Appeal’s decision in Jinpeng Group Ltd v Peak Hotels and Resorts Ltd.90 In this judgment, the Court of Appeal firmly rejected the approach taken in Salford Estates, reasoning that the “statutory jurisdiction to wind up a company based on its inability to pay its debts as they fall due unless the debt is disputed on genuine and substantial grounds” is “too firmly a part of BVI law”. The decision in Sian Participation endorses the ultimate conclusion of the Court of Appeal in Jinpeng.

This is not to say, however, that there was no divergence within the BVI courts regarding the correct approach to be taken. In a decision published in the months prior to the decision in Sian Participation, Mangatal J in Waterfront Property v Arius Litigation Funding 91 relied in part on the basis of a belief that the Privy Council’s earlier decision in Familymart China Holding Ltd v Ting Chuan (Cayman Islands) Holding Corporation 92 “although … concerned with a winding-up petition under Cayman Law on just and equitable grounds … made some very powerful pronouncements about the paramountcy of parties’ agreements to arbitrate” declined to follow Jinpeng.

Cayman Islands

The Grand Court of the Cayman Islands is yet to publish a judgment concerning this topic following the publication of the decision in Sian Participation. However, given the similarities between the arbitration and insolvency regimes of the UK and the BVI which were considered in Sian Participation and those of the Cayman Islands and the weight that Privy Council’s decision in Sian Participation will no doubt be given by the Grand Court, the decision in Sian Participation will almost certainly be found to represent the law of the Cayman Islands. Support for such a conclusion can be found in the Grand Court’s prior decision in Re BPGIC Holdings Ltd 93 which was handed down in the intervening period between the Privy Council’s decision in Familymart China Holding v Ting Chuan and its subsequent decision in Sian Participation. In Re BPGIC Holdings Ltd, Ramsay-Hale CJ refused to stay a winding-up petition based on a debt which was not genuinely or substantially disputed on the basis that the matter fell within the scope of an arbitration agreement.

Are damages available for breach of implied promise to honour award?

In the 2023 edition of this review we discussed the grounding and sinking of M/T Prestige off Spain and France in 2002 and how Butcher J confirmed awards of compensation granted by both arbitrators for contravention by the states of an equitable obligation to arbitrate (in an equal and opposite sum to the amount of the foreign judgment, effectively neutralising the judgment). We ended with a note of caution: “Given the amounts at stake, and fact that this is one of the first cases in which monetary remedies for breach of an equitable obligation were awarded, appeals are likely”. This prediction was correct. The English Court of Appeal in Kingdom of Spain v London Steam-Ship Owners’ Mutual Insurance Association Ltd (The Prestige) 94 has heard appeals from three judgments of Butcher J.95 We leave aside the CJEU/Brussels and human rights appeals and focus below on Spain and France appealing against the ruling by Butcher J that Sir Peter Gross and Dame Elizabeth Gloster (as arbitrators) had not erred in law by awarding equitable compensation for failure to comply with the obligation to arbitrate.96

The Court of Appeal agreed with Butcher J that an injunction could not be granted against Spain or France as the ban on such relief being given by a court under section 13(2)(a) of the State Immunity Act 1978 is clear. Section 48(5) of the Arbitration Act 1996 provides that a “tribunal has the same powers as the court ... to order a party to do or refrain from doing anything”. However, the Court of Appeal also found that it follows that that if a court does not have the power to grant relief, neither do arbitrators. That was confirmed by UK P&I Club NV v Republica Bolivariana de Venezuela (The RCGS Resolute).97 Therefore, the arbitrators’ views in The Prestige were incorrect:

“The judge and the Arbitrators were wrong to think that equitable compensation could be granted in this case, and the Arbitrators were wrong to think that equitable damages under section 50 could be granted in lieu of or in substitution for an injunction.”98

A further case that caught our attention, namely 廈門新景地集團有限公司 formerly known as 廈門市鑫新景地房地產有限公司 (Xiamen Xinjingdi Group) v Eton Properties Ltd and Another 99 is also part of a long-standing saga (involving arbitration and proceedings in the Hong Kong Court of First Instance, Court of Appeal and Court of Final Appeal). Common law actions to enforce an award are used when another route of enforcement is not available, for example when a country is not party to the New York Convention (unusual). In this case, judgment had entered by the Hong Kong court in terms of the award but the defendants applied to set it aside on the ground that performance was impossible (including because 99 per cent of subject matter land units had by then already been sold). Hence a common law action to enforce the award was commenced.

In the common law action, the plaintiff’s claims were dismissed at first instance. However, the Court of Appeal allowed its claim in respect of the first and second defendants’ breach of their implied promise, that they would honour the award obtained by arbitration in accordance with a valid submission under the agreement. At para 114 of the judgment of the Court of Appeal, Yuen JA explained that the essential ingredients of the new and fresh cause of action on an award, which is separate and independent from an action based on breach of the underlying contract, are simply a valid submission of the dispute to arbitration, an award in favor of the plaintiff, and the defendant’s failure to honour it. The plaintiff then had to elect between: (1) maintaining the statutory judgment; and (2) obtaining a judgment for damages for breach of the implied promise at common law. It opted for (2). In October 2017 judgment was entered against the first and second defendants, for payment of damages for breach of the implied promise. The trial on quantum for assessment of the damages finally proceeded in September 2023, 17 years after the award.

The court held that the plaintiff’s damages were to be assessed on the basis as if the award (ie the implied promise) had been performed at the time:

“I accept the counterfactual propounded for the Plaintiff, that damages should be assessed on the basis that the Plaintiff would, in 2006, have been in a position to have obtained the Shares in the 4th Defendant and be entitled to obtain the earnings from the development of the Land, this being the entire purpose of the Agreement at the time when it was made and as accepted by the tribunal in the Award.”100

The damages assessment thus involved an analysis of the award and what it contemplated as well as of the complicated relevant counterfactual. Interest at prime +1 per cent was allowed from October 2006 until the date of judgment (some of the time after the award having been disallowed by the judge excercising his discretion).

When tribunals did not but should have assumed jurisdiction

In Frontier Holdings Ltd v Petroleum Exploration (Pvt) Ltd,101 the Singapore International Commercial Court allowed an application to set aside jurisdictional ruling in which the majority of an ICC tribunal concluded that it had no jurisdiction to resolve the dispute before it. The case is the first reported decision in Singapore where a negative jurisdictional ruling was successfully challenged.102 The case arose under agreements (Petroleum Concession Agreements annexing a Joint Operating Agreement) relating to the exploration of oil and gas in Pakistan. The court held that in construing the agreements (under Pakistan law), the majority of the tribunal erred in concluding that it had no jurisdiction to hear the disputes. To the contrary, “on a proper construction, the PCAs and JOAs evince the parties’ intention for FWIO-PWIO disputes to be resolved outside of Pakistan” (rather than domestic arbitration in Pakistan). The court also concluded that the tribunal had jurisdiction over the arbitration, including the jurisdiction to determine the costs of the jurisdictional phase of the arbitration; and the merits of the dispute in the arbitration and made ancillary rulings.

Arbitrators and procedure

Failure to give reasons

Article 31 of the UNCITRAL Model Law (“Form and contents of award”) reads:

“(2) The award shall state the reasons upon which it is based, unless the parties have agreed that no reasons are to be given or the award is an award on agreed terms under Article 30.”

Singapore, like Hong Kong, has adopted the UNCITRAL Model Law. The Singapore Court of Appeal, in CVV and Others v CWB,103 , an appeal from an application to set aside an award under section 24(b) of the Singapore International Arbitration Act (breach of natural justice), noted:

“… case law on the duty of an arbitral tribunal to give reasons is sparse and we take the opportunity to make two observations about this area of the law. First, while Art 31(2) of the Model Law indeed places the arbitral tribunal under a general duty to give reasons, we caution that it is not settled in the case law whether a tribunal’s failure to give adequate reasons is itself a reason to set aside an award. …

Secondly, it is also not entirely settled what the content of a tribunal’s duty to give reasons is.”104

The Singapore High Court in DGE v DGF,105 which was an application to set aside a partial award under articles 34(2)(a)(i)(capacity) and/or (iii)(scope) of the Model Law, cited the above passages from CVV with approval.106 It went on to hold:

“… the Tribunal was not obliged to explicitly reject or explain why it rejected E’s evidence as a criticism against Fraunhofer’s visual inspection. A tribunal is not obliged to explain each step of its evaluation of the evidence and the weight attached to particular evidence, or to explain each step by which it reached its conclusion. Indeed, where a tribunal arrives at a conclusion of fact expressly on the basis of particular evidence, it is ‘unambiguously clear’ that the tribunal placed more weight on that evidence than on other evidence, and no clarification is required (TMM Division Maritima SA de CV v Pacific Richfield Marine Pte Ltd [2013] 4 SLR 972 at [100]–[101], citing World Trade Corporation v C Czarnikow Sugar Ltd [2005] 1 Lloyd’s Rep 422 at [8] and [9] and Hussman (Europe) Ltd v Al Ameen Development & Trade Co [2000] 2 Lloyd’s Rep 83 at [56]). The Award thus cannot be impugned on the basis that it did not contain adequate reasons for rejecting E’s criticism of the lack of randomness in sampling.”107

Confidentiality orders

In Beijing Songxianghu Architectural Decoration Engineering Co Ltd v Kitty Kam 108 the Hong Kong Court of First Instance refused to grant a confidentiality order preventing the public disclosure of information relating to an HKIAC arbitration. Before the court were parallel litigation proceedings against a party related to the arbitration respondent to recover “sums totalling about HK$253109 millions, or damages, for fraud, dishonest assistance and conspiracy to injure by unlawful means”. The decision confirms that while express statutory confidentiality protections under sections 16 and 18 of the Arbitration Ordinance Cap 609 are important, they are not absolute.

The decision also clarifies how to apply an important exception to confidentiality. Section 18(2)(a)(i) of the Arbitration Ordinance provides the exception that a party may disclose confidential information “to protect or pursue a legal right or interest of the party”. Similarly, article 45.3 of the 2018 HKIAC Administered Arbitration Rules (which governed the arbitration) provides that a party is not prevented from disclosure of such information to protect or pursue a legal right or interest of the party. Deputy High Court Judge KC Chan discussed the English Court of Appeal case of CDE v NOP 110 (discussing a similar provision under the LCIA Rules) and in particular cited Males LJ at para 50 thereof with approval and adding his own emphasis:111

“50. That said, we make clear that the considerations which led us to conclude that the judge was right to hold the case management conference in private will not apply, or at least will not apply with anything like the same force, to the privity application. That will be an application for summary judgment at which the court will be required to adjudicate on the merits of the dispute. Moreover, if the court holds that the hearing should be held in public, there will be no question of any breach of article 30.1 of the LCIA Rules. That rules entitles a party to put the award in evidence before a state court in order to protect or pursue a legal right. That is what the clamant will do. If the applicable procedural rules mean that the court will sit in public to hear that application, these is no breach of article 30.1.”

Deputy High Court Judge KC Chan concluded that CDE v NOP did not assist the defendant. Rather, it reinforced that disclosure to protect or pursue a legal right of the party, as provided by section 18(2)(a)(i) of the arbitration, does not amount to a breach of the arbitral confidentiality and that arbitral confidentiality being so excepted by section 18(2)(a)(i), it fell on the defendant to satisfy the court that there were otherwise cogent reasons in this particular case (save arbitral confidentiality) to justify a departure from open justice, or that due administration of justice requires the principle of open administration of justice to be compromised.112